By Rebecca Petty

The abduction of a child is every parent’s worst nightmare. In the event of a child abduction, that child can be taken away from their family at the rate of a mile per minute. Within an hour of an abduction, a child can be as far away as 60 miles, staggering if you think about it in those terms. In the event of a child abduction, swift action must be taken and law enforcement called immediately. Many people are still under the misconception that law enforcement cannot be called in until the 24 hour mark is reached, but this is simply not the case anymore. Sadly, we have all learned that time is of the essence in the case of a missing child. In 76 percent of child abduction murders, the victim was killed within 3 hours of the reported abduction, and in 89 percent of child abduction murders, the victim was killed within 24 hours. (Gregoire, C., US Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Deliquency Prevention. 2006)

The importance of contacting law enforcement cannot be stressed enough. In the event of a true child abduction, a myriad of people will become involved in the search for the missing child including the community in which the child lives. The people in the community can help immensely in the return of a missing child by holding candlelight vigils to bring awareness to the missing child and by assisting in the search for the missing child. Community involvement is sometimes the key in the return of the child, whether alive or deceased.

May 15, 1999, 12-year-old Andria “Andi” Nichole Brewer was babysitting at her father’s rural Arkansas home when a knock came at the door. Her two younger stepsiblings said it was “Uncle Karl,” and that he said her grandparents were ill and she must immediately come with him. Brewer left under the assumption that she was going to her grandparent’s house. A three- day, state-wide search ensued, which included local and state police, the FBI, and hundreds of community volunteers who collectively scoured the rural area in the Ouachita Mountains. The frustrated Sheriff, Mike Oglesby, commented that Andi seemed to have disappeared off the planet.

The nightmare is not knowing what happened to your child and not knowing who did these terrible things to your child. (Walsh, 1997). “Uncle Karl,” an uncle by marriage, confessed to kidnapping Brewer and taking her ten miles away to Cove, Arkansas. He drove her down an old logging road west of town where he brutally raped and strangled her to death. He then covered her nude body with scrub brush and threw her clothes in Buffalo Creek. He then proceeded to his parent’s house where he shared a cup of coffee with his father and then, upon a frantic call from his wife, returned to help search for Brewer. He assisted in the search for her for three days and finally confessed to the state police and FBI upon the failing of a polygraph test, shortly thereafter, he led authorities to her body.

Andria “Andi” Nichole Brewer was my daughter. Her short life set my own life on a path of creating a legacy for my daughter and made me realize that the only way to overcome victimization was through empowerment and education. It became my passion to ensure that this sort of thing never happened to another child. However, first on the agenda was something that only stood in line behind burying her. That was to attend the capital murder trial for the man who murdered her.

Abduction and Capital Murder

On Tuesday, May 18th 1999, Karl Douglas Roberts was charged with the capital murder of 12-year-old, Andria Brewer. He pled not-guilty in front of a stunned Polk County Circuit Court in the small town of Mena, Arkansas. Prosecutor Tim Williamson was set with the task of not only dealing with Brewer’s family, but also with the task of controlling a community who wanted to hang Roberts on the front lawn of the courthouse. Death threats were coming in for Roberts and even his own family cowered in fear in their homes. Williamson did his job to the best of his ability considering he had only prosecuted one capital murder case and never a case involving a young child. This quickly became a learning event for everyone involved, the State of Arkansas, the community, law enforcement, and the victim’s family. Some of the larger issues were regarding the media, and Williamson handled them with grace. Additionally, to deal with the victim’s family, Williamson assigned Jo Mitchell, a victim advocate for the Prosecutors office. She helped answer tough questions and was there for the family when they needed emotional support. It was after strong support and encouragement from Jo Mitchell that I realized that, one day, I could help others and be there for the hurting families. I was treading on a path few had walked and had empathy for people I never felt before. It was then my stirrings for helping others were born.

Coping with Becoming a Crime Victim Overnight

Coping is one of the hardest things to learn after becoming a victim of violent crime. Trust is nonexistent, hope is out the window, and belief in God is questioned. There are many things to learn. One of the most astounding things I learned was how evil the world could be. Being raised in a middleclass family and not being associated with any type of crime, I was stunned to learn that the average victim of abduction and murder is an 11-year-old girl who is described as a low-risk, “normal” child from a middle-class neighborhood who has a stable family relationship and whose initial contact with an abductor occurs within a quarter of a mile of her home. (Gregoire, C., US Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Deliquency Prevention. 2006). My knees came out from underneath me as I learned that my young daughter had been brutally raped before being strangled. I will never forget the prosecutor telling this me this fact and his face becoming shadowed to my view as I began to pass out. This happened while picking out a casket, too. When the door opened to the room lined with about twenty caskets for me to choose from that shadowy darkness enveloped me once more and my knees again became weak.

A child’s funeral is awful. The way I remember it was that all of the faces seemed out of place. People that I knew from every aspect of my life had filled the room. My parents. My church friends from Oklahoma. There were people who lined the wall. I recall wailing. Someone said I wailed, but I do not remember this. All I remember is a casket. Pepto Bismol pink. And I remember Amazing Grace, and the drone of a sermon, and pink balloons, and watching that Pepto Bismol casket lowered into the ground. But, I wanted only one thing. To be inside of it, holding her, caressing her, telling her I was sorry I hadn’t been there to stop this, and to tell her I loved her. This was truly the moment when I knew that no parent should ever have to bury a child. It was then I knew that I must be the one to advocate for victims of crime and children.

In the State of Arkansas, a person commits capital murder if they commit murder in the commission of another crime. (Arkansas General Assembly. 2013). In this case, Williamson decided to charge Roberts with the rape and murder. He left the abduction out of the charge in the rare event that something went awry at the trial and he needed to charge the abduction at a later time. In the fourteen years since this crime was committed, he has never had to charge for that felony kidnapping. Karl Douglas Roberts was charged with first degree capital murder and the only hope he had was to receive life without parole. This wasn’t likely in a rural Arkansas county where truly, as politically incorrect as it seems, even blacks were told not to be seen in town after dark. Seems there were two things not tolerated in Polk County, blacks and child killers, although I never could understand the racism issue and blamed it on the character of the Deep South. Wanting to kill a child murdered was another story.

Watching Roberts being led into that courtroom, I could only think of one thing. Andi was dead and cold and he was warm and alive and beginning the fight for his life. Hate had a new meaning, and it was standing in front of me. He was vile and disgusting and hate consumed my heart. I knew even then that this wasn’t right and I was in for the biggest challenge of my life, to live through a capital murder trial.

Facing a Capital Murder Trial

Prosecutor Williamson informed the Brewer family that it would be about a year for the trial to begin. And true to his words the trial began exactly one year to the day Andi was kidnapped, raped and strangled to death. Prior to the trial, I had to admit to myself that I knew absolutely nothing about the criminal justice system or how it worked. This was when my training and the journey of empowering myself began. The wealth of data on the information superhighway became my best friend and was where my true learning started. I became a self-taught lawyer, advocate, and law enforcement guru. Over the previous year, I had already become an advocate of sorts. People began to tell me things such as they had been raped as a child. Whenever another child went missing, the news media would reach out to me for comment as though I had all the answers. I found myself speaking in front of crowds of parents, law enforcement, and my community, and teaching them the dangers of predatory crime against children. I was invited to Washington D.C. to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to become a member of Team HOPE, a group who offers peer support for families with missing or sexually exploited children. And in this, I taught and memorized the language of the law, what law enforcement lingo meant, some of the Latin that was used in terms of the law, actus reus (guilty act), per curium (through the court), modus operandi, (manner of operation or M.O.), and habeas corpus, (to secure the person’s release unless lawful grounds are shown for their detention), the latter is a word that often haunts crime victims for many years in death penalty cases.

The process of grief is difficult. Asking, “why me,” or “why my child,” is a normal human reaction, but not a human reaction that is welcome. It is the wee hours of the morning that are the most difficult and suffering from post-traumatic stress leaves a person exhausted.

Something learned about “why,” was to question whether it was nature, was Roberts some freak of nature? Or was it nurture?

What always is a debate, is it a nature or nurture thing? I can say from the people who I have interviewed, on death row or in prisons around the country, most of them will have some type of violence, psychological, physical violence, sexual violence in the background. However, I’m kind of tough on this because I still don’t believe it should be a mitigating factor, they still have the ability to make choices and [use] free will and they’re making these choices and it’s the wrong choices. (Douglas, J., Olshaker, M. 1999)

To sit through a capital murder trial and realize what a predatory monster did to your child is heart rending. And when Karl Douglas Roberts was sentenced to death for murdering my 12-year-old daughter, I thought that justice had been served. I was wrong on so many levels. I have since learned this was only the beginning of many years of appeals and a lot of work for the State of Arkansas, ACLU, and many appellate judges. All in all, I have learned, a death penalty case, is a cash cow.

Becoming an Advocate for Children and Victims

Being taken seriously became a big area of concern for me. I began to speak out on many issues advocating for victims and children. I found myself in court with victim families, doing media interviews, along with photographing and fingerprinting children at safety fairs. My face and my child’s face became synonymous with keeping children safe. The only problem was that I always seemed to be the mother of that “poor little girl.” People sometimes were overcome with grief when they saw me and at other times I heard people talking bad about all the money I was making by promoting my dead child. It wasn’t true, I never made a dime, but I knew that I had to be taken more seriously. I realized that my lack of education made me seem weak. Even though I had been invited by the White House to discuss the issue of a National Amber Alert in a private roundtable discussion with President Bush who ultimately signed it into law, I still knew I had to do more. I needed a college education. I was scared to death when I enrolled in the Criminal Justice program at Tulsa Community College part-time. I began what has been a ten year trek of trying to raise a family, be an advocate, and a student. However, I always knew someday I would complete my degree. Being an advocate for victims and children has opened many doors for me. However, I will never shy away from saying that if I could have one more second with Andi, I would give it all up in a heartbeat. It has always been about creating a legacy for her, not me having a job. But, the more I talked about the case, the more people wanted to hear what I had to say. And they listened.

Still Learning the Ropes

Empowering myself through education has been the key in this tough field. It has been fourteen years since the death of my daughter and I am still fighting for her legacy. It is surreal to think that Andi would be nearly 27-years-old now. For fourteen years, I have fought for crime victims and children. I have met President Bush, shared Andi’s story with him. I have shared her story with Jamie Lee Curtis, Bryan Cranston, Patrick Dempsey, Morgan Freeman, and sat on Oprah’s couch and told her as well. I have become a consultant for the Department of Justice’s Office for Juvenile Justice and Delinquency as well as Fox Valley Technical College. I train law enforcement on the family perspective of child abduction, and I suppose that does make me the expert now. I have lobbied on Capitol Hill for the Adam Walsh Bill and become friends with other advocates, Colleen Nick, John Walsh, Marc Klaas, and Ed Smart, all victims who taught me through the school of hard knocks.

I am also glad to report that nightmares do not come as often as they used to. Fourteen years is a lot of time to heal. I have worked hard, and my skin had to become tough in the face of naysayers who have told me to “let the dead rest,” and that I should be fighting “against” the death penalty, to which I reply, “I was not a juror in this case.” I have faced many challenges and obstacles and in December, I will be proud to walk across the stage and finally, finally, finally receive my bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice. However, I am not stopping there. I plan on advancing forward to graduate school. When that is over, politics seems a logical path for me. City council, state representative, senator, governor?

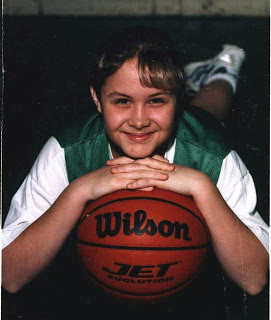

The event that led me to this career path, is not something I would wish on anyone, the price is too high and no one should have to lose a child. That being said, I won’t stop, a legacy is still in the making and it is for a 12-year-old girl everyone called Andi. A girl who had a mega-watt smile and an infectious giggle. She was taken from this planet far too young and will always remain in my mind as a gentle apparition, one forever trapped at the tender age of twelve. But she will have a legacy. I will see to it.