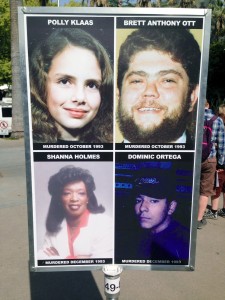

Soon after my daughter Polly was kidnapped on October 1, 1993, she became known as America’s child. Donations to assist and facilitate the search poured in from the far corners of America. Violet and I founded the nonprofit Polly Klaas Foundation (PKF) to best administer funds and to protect ourselves from potential speculation that we would misappropriate money donated to help find Polly. We wanted to be proactive in ensuring that the focus remained on finding Polly.

Nonprofit organizations are governed by a Board of Directors. For the PKF we chose individuals who were prominent during the early days of the search. In fact, Violet and I left much of the organizing to those very people as we immersed ourselves in the search for our missing daughter. We named the organization after Polly because the donations, the focus and the hope was all about my daughter. Before the month of October, 1993 ended the Internal Revenue Service had conferred nonprofit status on the PKF.

Board responsibilities included fundraising, program development and financial management. Generally, Boards of Directors do not become involved in the day to day running of an organization. Those are tasks that are left to the nonprofit’s President, Executive Director, and staff.

Upon learning of Polly’s tragic death on Dec. 4, it was our intention to lobby for laws that would protect children, use the remaining $283,000 to help find other missing children, and continue fundraising, but the PKF Board made it difficult to accomplish these objectives. They seemed more concerned about protecting (their) assets and enjoying the status of sitting on the Board of a high profile nonprofit organization. This resulted in deep and ingrained tension between Violet, me and the Board. Violet, who was not a member of the Board, was not allowed to attend meetings. At these meetings I often found myself with very few allies.

Janet Reno’s visit to Petaluma in July, 1994 was a good example of my conflict with the Board. I had secured the United States Attorney General to speak at a town hall meeting to discuss crimes against children. As a result, the PKF Board accused me of grandstanding. They reasoned that if the Attorney General’s visit was a success I would receive the glory, but if it failed they would take the blame. After Ms. Reno’s visit, which went very well, drew massive media attention, and filled the hall at the Petaluma Community Center, relations between the Board and me became even more strained.

President Clinton signing the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994

Within a year of my daughter’s kidnapping several events foreshadowed our rocky nonprofit experience and lonely crusade. On September 13, 1994, I stood on the podium with President Clinton at the White House when he signed The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The President gave me the first pen that he used to sign the bill. The Crime Bill provided for 100,000 new cops, allocated $6.1-billion in prevention funds for at risk children, and nearly $10-billion for prison construction costs.

Within days of my invitation to join the president the PKF Board informed me that I was no longer allowed to pursue criminal justice legislation. They argued that a non-profit organization is prohibited from advocating for new laws. They knew that this was not accurate. What was happening was the PKF Board had created a mission limitation that did not include legislation. Violet and I believed that Polly’s legacy had to include powerful public policy positions that would protect other children from her tragedy.

Without hesitation and a sense of urgency a separate non-profit application to create what would become known as the KlaasKids Foundation had been submitted from which to lobby, advocate and promote legislation. The PKF Board said that I had created a conflict of interest by finding an avenue that would allow me to pursue goals that they forbade me from pursuing. This was their justification for expelling me from the nonprofit that bore my daughter’s name. Ironically, the current PKF website states that a primary objective is to effect legislation which, “Will ensure that children can be safe in their own homes and communities.”

Within one year and 20-days of my daughter’s death, on October 21, 1994, without my knowledge, the PKF Board secured a trademark for the name Polly Klaas. My daughter’s name now belonged to the Polly Klaas Foundation.

Within a month of trademarking my daughter’s name, while Violet and I were out of town, the PKF Board voted me off the board during a secret meeting. This was the first Board meeting that I did not attend since the inception of the organization. Over the telephone the Board President informed me that I was expelled from the nonprofit organization that bore my daughter’s name. I felt that I had lost my daughter yet again. Violet and I were no longer welcome at the Foundation that we had created and hoped would become Polly’s legacy. We had been betrayed.

When Violet and I were locked out of the PKF we had $2,000, a fledgling nonprofit that would become the KlaasKids Foundation and knives in our backs. We felt that we had lost our daughter yet again. With a sense of urgency we believed that there was no time to lose, because otherwise everyone would forget. We struggled. Violet worked a full time job; I volunteered my time to KlaasKids. We lived frugally, turning our home into an office. We worked 18-hour days writing, advocating, traveling and otherwise pursuing our window of opportunity. Fortunately, our voice and our passion were being heard on television, radio, in the op-ed pages of newspapers and at KlaasKids events throughout the country.

It was through KlaasKids that we built a solid reputation for action and accomplishment. Meanwhile the PKF struggled. With just a few months of operating expenses left in their account, PKF launched a high profile car donation program. For the next several years a confused public donated millions of dollars’ worth of vehicles in Polly’s name despite the fact that the PKF produced minimal results.

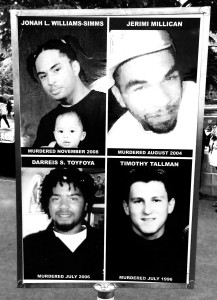

The sense of betrayal continues to this day. Today it was brought to my attention that there is an organization exploiting missing Morgan Hill cheerleader Sierra LaMar for profit. The families who suffer and are victimized by the loss of their children are victimized yet again by those who steal, exploit or profit off of personal tragedy. I have witnessed too many instances of family members pursuing a legacy in honor of their loved one only to have their organization hijacked.

Shame on them! People or groups who oust family members betray the memories of crime victims by heaping insult upon injury. Sometimes I can still feel the knife in my back, but I take solace in the knowledge that Polly was my child and that her legacy is my destiny. KlaasKids may not bare Polly’s name, but we have created her legacy and given meaning to her death. One of the lessons of betrayal is to remain strong and not allow it to tarnish our character.

I never expected that we would hit this milestone: Sierra LaMar has been missing for a year! That means that her family has endured four seasons of not knowing where their beautiful daughter/sister is. Their Saturday morning ritual has become routine. Get up very early, put on your best face, grab a mug of coffee, drive to Morgan Hill and hope that when you turn into the Sierra Search Center yours isn’t the only car in the parking lot. To date those specific fears have not been realized, but that doesn’t mean that there’s not plenty left to be fearful of. Marlene LaMar recently told me that, “It has been a long journey, and the most difficult thing is not having the answers which makes waiting feel infinite. The loss and pain has been indescribable.”

I never expected that we would hit this milestone: Sierra LaMar has been missing for a year! That means that her family has endured four seasons of not knowing where their beautiful daughter/sister is. Their Saturday morning ritual has become routine. Get up very early, put on your best face, grab a mug of coffee, drive to Morgan Hill and hope that when you turn into the Sierra Search Center yours isn’t the only car in the parking lot. To date those specific fears have not been realized, but that doesn’t mean that there’s not plenty left to be fearful of. Marlene LaMar recently told me that, “It has been a long journey, and the most difficult thing is not having the answers which makes waiting feel infinite. The loss and pain has been indescribable.”